The Y2k38 Bug: The biggest news craze of the year 2038

As you might know, I co-organise a PHP meetup called: PHP Antwerp. Some time ago we had one of our talented speakers: Joeri Sebrechts talk about “What every developer should know about time, no excuses“ (If you ever have the chance to see it, I wholly recommend it). In this talk, he mentions briefly the Y2k38 problem. A bug that will wreck havoc on systems that store time in Unix epoch timestamps.

Wait, this sounds familiar.

That’s because it is …

For those of you who weren’t fully sentient around the time everyone partied like it was 1999 (for the second time). The big problem around that period was the Y2K bug. Quickly summed up, the Y2K bug was due to people storing years in a 2 digit form like 88 or 67. Now when the year ticks over to 2000 (or every 100 years) they would reset to 00 or 01.

At the time there was a lot of media buzz around the topic. Planes would fall out of the sky, hospitals would shut down, society would collapse. When the clock eventually ticked over to the new millennium, everything seemed to be still fully functional (including the bleached spiked hair styles). The media quickly resumed to the new hot topic and it all quickly died down. The entire event would be remembered as a hoax.

But it absolutely wasn’t. In Gary Hockin’s talk “Using Open Source for Fun and Profit” (One of the best talks I’ve ever seen) he briefly talks about working together with other engineers to check applications for the bug and mitigating the issue (yes he is that old). The truth is that it costed a lot of hands and a lot of capital to sort out.

And even then we didn’t made it out without a scrap. Credit card machines stoped working, 2 unplanned abortions ensued, An alarm sounded in a nuclear powerplant in Japan and even the US Naval Observatory was touched.

What makes 2038 so special?

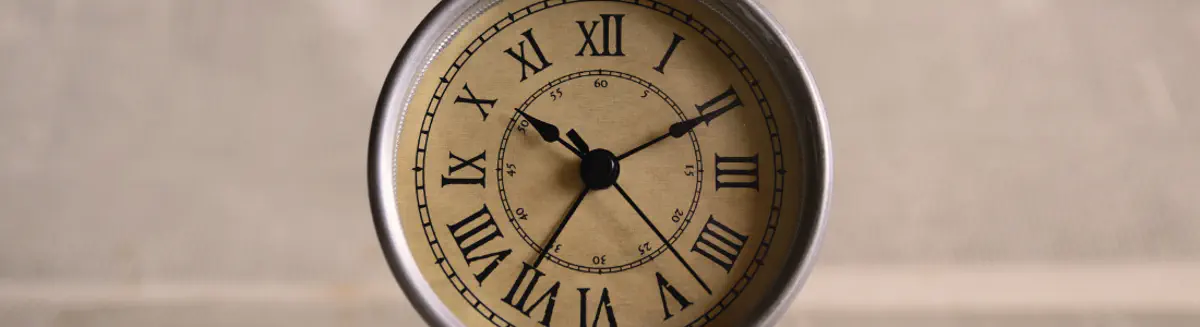

So yeah, Y2K happened because of a logical problem, but 2038 sounds a bit random… That’s because we are looking at the date in a “human readable” form. If we store the date as a Unix epoch timestamp, a form of timekeeping that counts seconds forth from 00:00:00 1 January 1970, we would get 2147483648.

Again, for some people this might still look like a very random number, but that is more than half of the maximum range an integer can take on a 32-bit system. An integer has a positive range and a negative range. This allowed us to go to dates before the year 1970. Half of its range is negative and half of its range is positive. If you count these two halves up, you might see that we are dealing here with an integer overflow. More precisely after 03:14:07 UTC on 19 January 2038.

It is possible to change the positive and negative range of the data. However you can not extend it, but you can shift it forward or backward. For example, a company that deals a lot in old data might have shifted the timestamp further back. Giving it less reach in times after 1970.

This means that the Y2k38 might not appear for everyone at the same time. Or even in the year 2038.

What happens then?

Mostly the same situation as Y2K, but in this case we don’t go back to 1900 but we go back to 13 December 1901. The good news here is that we jump from a Tuesday to a Friday. The bad news is that banks might calculate negative interests, airports might send wrong routes to planes, basically everything that has a critical function related to timekeeping might be in trouble.

Why do these things happen?

When we look back at the Y2K bug, it all seems kinda silly. Why would you store a year in a 2 digit form … why couldn’t you anticipate this issue … The same question arises for Y2k38, you know the integer will someday run out in you 32 bit system. So why use it?

There is a bit of survivorship bias going on here. Take for example the project you are currently working on. It can be a long term legacy project, a cool new startup idea or a small advertising project. Will that be around for 5 years? 10 years? 30 years? It’s very hard to tell right now, technologies change, the product changes. Preparing your code for an issue that might show up in 30 years sounds irrational. Yet somehow some systems keep running without that refactor for years.

premature optimization is the root of all evil (or at least most of it) in programming. - Donald Knuth

What software is at risk at the moment?

It is very fussy to give a full list of all systems at risk. But it is safe to assume that almost all systems that count on Unix timestamps in a 32-bit environment will be at risk.

This includes operating systems, databases, embedded systems …

Should I start digging a fallout shelter?

Yes, yes you should. Would be a kickass ice breaker. “Did you know I have a fallout shelter” ? Actually scrap that, sounds kinda creepy. You would a least not need one for this bug. Just as with the Y2K bug, this one will pass. There will be a lot of money spend. A lot of people will earn a lot of money. But in the end, it will mostly be resolved.

In the meantime, it seems best to not store your dates in Unix timestamps if you’re on a 32-bit system. For all you know your software might still run on some old machine in 20 years.

further readings... in [Software]

Taming Chaos: Handeling vendor based architecture

I’ve noticed a huge shift in the architecture of big companies in the last few years: companies are shifting from in-house development …

Read EntryI think we should reimagine how we see architecture principles

To me, it always seems strange that in a world that thrives on innovation and constant change, every architectural department tries to …

Read EntryThe Goldilocks strategy: Finding 'Just Right' in Good, Fast, and Cheap

Picture this: it’s a Tuesday afternoon. You are called into a meeting room by your teamlead. He’s conversing with a client about …

Read Entry