The economics of clean code

“The only way to make the deadline — the only way to go fast — is to keep the code as clean as possible at all times.” — Robert C. Martin

I’m afraid I have to disagree with this statement. Let me tell you why.

What is clean code

There seem to be many opinions surrounding clean code. Some people have an entire architecture of how code should look. Others stick to the actual layout of the code, or length of a class while even others vaguely point towards Robert C. Martin’s books.

One thing is clear; it’s something that’s really on a lot of developers mind. Clean code makes projects more comfortable to work with and improves shelf life. It’s the antagonist of vile legacy codebases that are unmaintainable.

Then why does business always treat it as a secondary objective? Do they just don’t get it?

Business needs vs developers struggles

Clean code and architecture indeed allow businesses to have a more maintainable product. But I’m sure you would agree that before you can have a maintainable product, you should first strive to have an actual product.

The foundations of a product are undoubtedly essential; they dictate the mindset of the months/years to come, but they also take a tremendous amount of time. Time in which the project isn’t moving. If the project isn’t moving, we are not generating revenue. Every start indeed requires a startup cost, but we also need the lights burning and the espresso flowing.

This entire mindset was partly the start of the agile movement. Build a minimal viable product, get it to the market fast; see if there is a demand, iterate.

It’s where that horrible motto from Facebook comes from: “move fast and break things”.

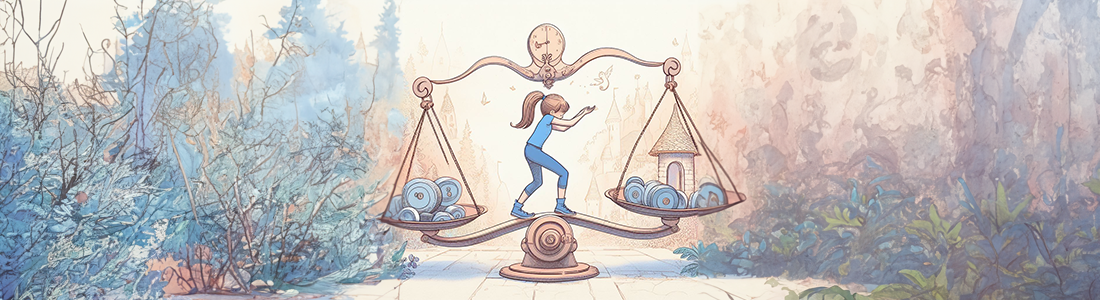

It seems we’ve come to an impasse: the tech side wants a well balanced and nutritional dinner, while the business side wants fast food

Technical debt

So yes, that mindset results in those paymentsService god classes that are 5000 lines long and nobody dares to touch. Controllers that speak directly to databases; in short, technical debt.

It seems we’ve come to an impasse: the tech side wants a well balanced and nutritional dinner, while the business side wants fast food. But it’s essential to realise that it’s not a tug of war. It’s better to look at it as a process that needs some leniency from both sides.

As said in the previous chapter, you can’t build a product in a vacuum. You need to stave it against the market. Otherwise, you risk much capital against untested ideas. Investing a third of your budget before you even can think of a front-end might be a bit risky from a business standpoint.

On the other side, keeping acquiring technical debt is also not a way forward. You will, indeed have a quick start. Implement features in days instead of weeks. … till you can’t anymore. Just like financial debt, technical debt will eventually catch up with you. And it can end your business just as quickly. It’s great to have a product that’s a perfect market fit, but if you can’t keep up with your competitors cause your application is too slow, or features can’t be implemented quickly enough due to the technical mess, you will lose out.

So treat that technical debt as you would financial debt. Use it to invest it into your project. But keep track of it and pay it off. I would recommend this post from Mathias Verraes on how you can do this.

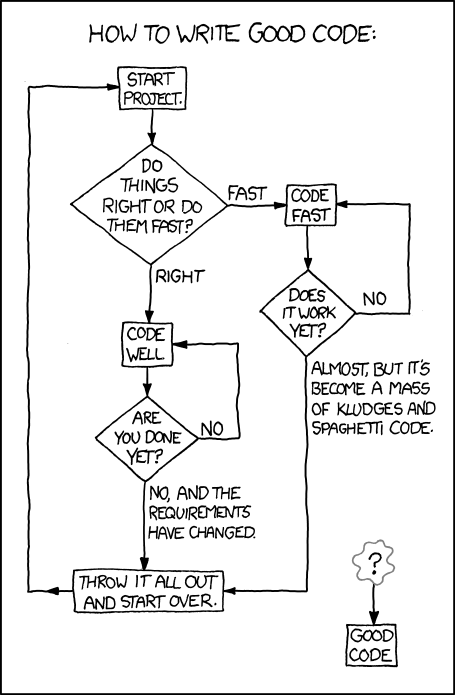

Image courtesy of XKCD (https://xkcd.com/844/)

Long term thinking vs quick wins

You also have to keep the scope of the project in mind. Some people build systems with the mindset that it might blow up anytime and we’re going to need to support this for years to come. Other people start big projects without tests and pretend that they’re going to write them in the future, “when there is time”.

It’s critical to strike a decent balance here and reevaluate the scope and market position of the product at regular intervals. This evaluation should not be only on the business or technical side; this is a team effort and should also be communicated that way.

My takeaways (TL;DR)

It’s essential to realise what you are building and the impact it will have in the near and far future. Keep the short time roadmap concise and don’t over-invest (financially and technically) but also don’t try and outrun the liabilities you are taking on along the way.

Keep communication of the status and impact of the project open towards the entire team, and reevaluate these values on a regular timeframe. Adapt your level of technical investment according to these projections.

further readings... in [Software]

Taming Chaos: Handeling vendor based architecture

I’ve noticed a huge shift in the architecture of big companies in the last few years: companies are shifting from in-house development …

Read EntryI think we should reimagine how we see architecture principles

To me, it always seems strange that in a world that thrives on innovation and constant change, every architectural department tries to …

Read EntryThe Goldilocks strategy: Finding 'Just Right' in Good, Fast, and Cheap

Picture this: it’s a Tuesday afternoon. You are called into a meeting room by your teamlead. He’s conversing with a client about …

Read Entry