I think we should reimagine how we see architecture principles

- Enterprise architecture , Software , Managing technology

- August 17, 2024

To me, it always seems strange that in a world that thrives on innovation and constant change, every architectural department tries to implement a rigid set of principles that stay in place for years.

From software design patterns (think SOLID, DRY, …) to the more strategic layer (think TOGAF, PRINCE2, …), these principles seem to have been around forever. Is anything really timeless and forever the same?

The Braun story

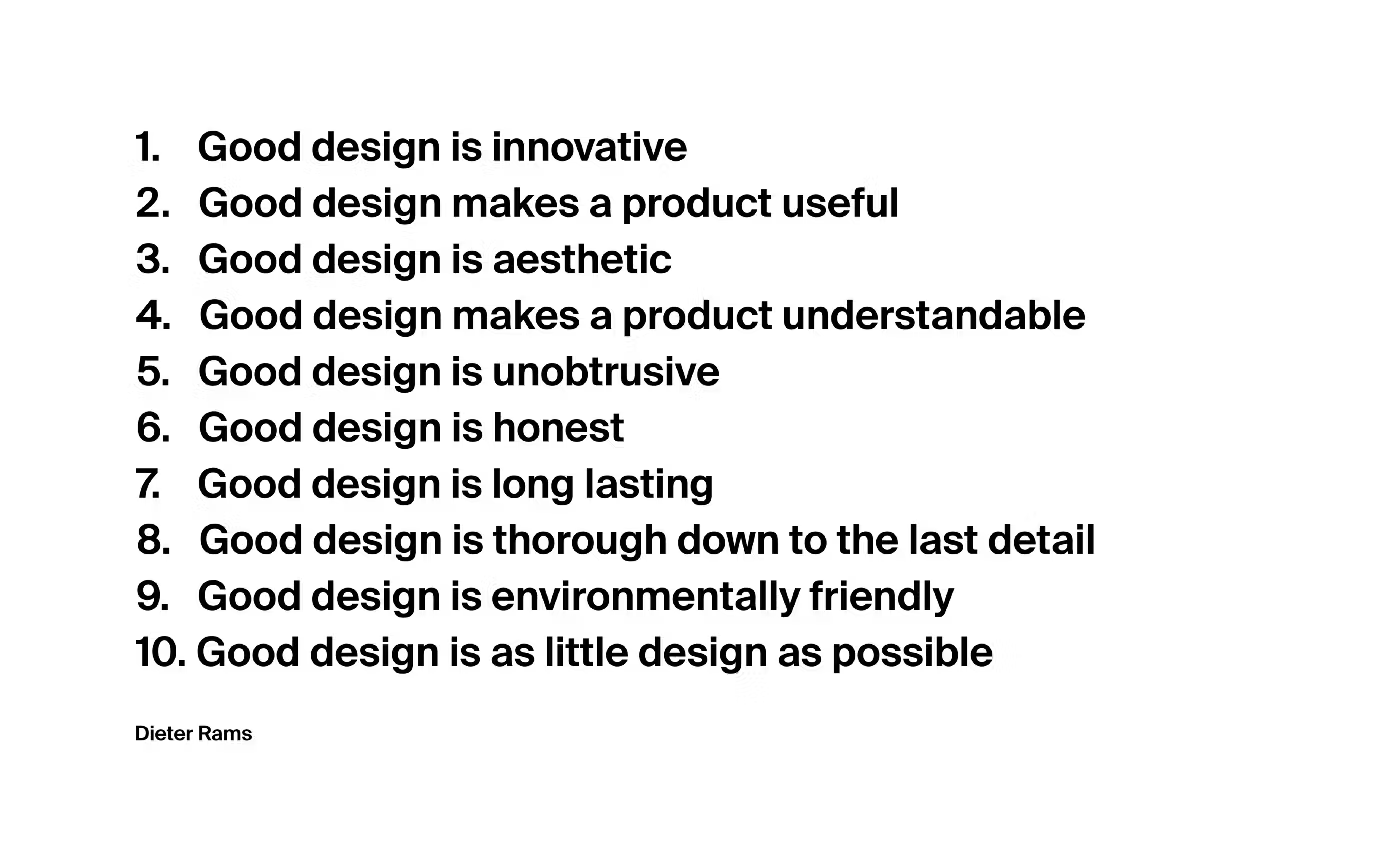

So, I’m a bit of a design nerd. I like architecture and product design, so a few years ago, I visited the Braun-Sammlung Ettel Museum für Design (Big recommendation ) in Berlin. It’s a museum dedicated to the iconic design of Braun and, for a big part, the work of Dieter Rams. The story goes that Dieter Rams developed ten design principles that all their products needed to adhere to.

These principles are painted in Helvetica (of course) on the museum’s wall.

Braun made gorgeous, functional, and valuable products, with Dieter Rams at the helm in the 60s - 90s. However, once globalization came knocking in the 90’s and cheaper Chinese products flooded the market, Braun got in financial trouble. Dieter Rams and the principles left, and now Braun is a totally different company that is unrecognizable from the pre-1990s Braun.

There is a giant wall of electric shavers in the museum—a timeline of the evolution of the device with the release date under them. In a matter of seconds, you can look at that timeline and see when the design language changed; it’s shocking.

To me, this made a big impression. I walked away from that museum and was struck with what a huge shame it was. If only they kept that vision, we could still have houses full of iconic design pieces mass-produced. The world would be such a nicer place.

I now think that’s the totally wrong lesson to learn from that story.

The world is not a static place

The lesson to be learned from that story is that if Braun continued with what they were doing, they would have gone broke. The market was more interested in cheaper products than Rams’ design pieces. Making a cheap product with the principles described above is very hard.

We might have the same conversation about some famous principles in technology land. SOLID for example is often cited as the golden standard of software development (even if these days it’s highly criticized). There are, however, languages like Go and Rust that are becoming increasingly popular and are being adopted by big organizations where applying principles like SOLID or DRY is tough and probably not practical (SOLID is very focused on typed object-oriented programming languages, design philosophies that RUST and Go don’t share). I’m not saying that these languages are going to take over from the likes of Java and C#, but it’s hard to deny that there is a wave of different design ideas getting a foothold in the landscape (just think of the functional programming ideas like Map and Filter that are these days standard in a lot of languages)

Moving a layer higher, we see the same things happening, albeit much slower.

The TOGAF principle of “Data as an Asset: Because all decisions in an enterprise are made based on data, all that data needs to be carefully organized and managed. Everyone in the enterprise should know their data is reliable and accurate.” for example.

This one didn’t survive the first LLM chatbot. It turns out that just like in the Braun story, it is nice to have principles that enforce quality (in this case, data accuracy), but people prefer the ease of use of “good enough”

How to still have the benefits of these principles

The interesting thing about all this is that if you move to another different layer in the organization, a typically long-term vision layer: the strategic layer, you would expect a more static view. Yet here we see that they re-evaluate their vision of what to do every few months.

Ideas like “Everything cloud” and “Reuse before you Buy, Buy before you Build”, are very known examples that have been around for a while now. And they are, of course, far from free of criticism. They are, however, more recent than SOLID.

How is it that our traditionally seen as a slower layer in an organization (a layer that is focused on long term and not focused on weekly changes) has fresher principles than our operational layer, which is constantly changing?

Well, the answer is obviously that they refresh it every six months and adapt it to the current market and challenges.

If you make big architectural principles that everyone has to follow and never change, you are also stuck with those ideas for years to come. This is how you create products that need workarounds to fit into an ever-changing environment.

Take, for example, an organization that goes all-in on microservices. They made that decision cause it made sense for their needs and scale. Now, at some point, the product grows, and they need to catch up with the overhead versus delivery time. They have decided that the microservice idea is what they do so they stick to it and hire more ops people. This might be the solution, but chances are that they might run into the same problem in six months.

However, they might also re-evaluate the microservice idea every six months. See where the overhead comes from. Blow up one of the microservices to a service that handles multiple things (move away from the Single responsibility principle in SOLID, a deadly sin in the microservice world) and meet the product needs. Once you have one big service and a bunch of satellite microservices, you can either keep the situation like this and create specific microservices for specific needs or start to integrate these microservices back into a monolith; you can call it endocytosis architecture (my girlfriend is a scientist, I’m trying to use big words to impress her).

What we’ve done here is adapt the product’s architecture (the technical side, at least) to the different stages of the product lifecycle.

Now, this is a huge example. Going from a microservice to monolith architecture is not something you will do in a week. You also don’t want to make changes from this size every year. But it is essential to at least be open to these ideas.

On a smaller level, we could look at DRY (Don’t repeat yourself). I’ve seen so many developers take the DRY idea way too far. They end up with hundreds of interfaces (Something I’ve seen often in Go) or small classes that do something tiny that is referenced twice.

DRY is an excellent idea if applied sensibly and on the correct scale. For example, you could start your product by not abstracting, and once you have a product that brings value, you could begin to implement DRY. Again, we fit our principles to the environment and don’t mindlessly follow principles that might be meant for a different product, time and/or place.

So, the short of it is that principles are alright. They create a sensible default. Just ensure that the principle still applies to what you are doing. And maybe don’t write them on the wall, even if it is in Helvetica, or you might end up in a museum celebrating a time when you were a perfect market fit.