Taming Chaos: Handeling vendor based architecture

I’ve noticed a huge shift in the architecture of big companies in the last few years: companies are shifting from in-house development to third-party applications, shedding the traditional ‘Not Invented Here’ stigma in favor of external innovation.

It is not hard to understand the rationale behind it: you can use the best tools in the market 1 to handle parts of your business, the vendor handles all the technical maintenance, and they even keep improving the software, and most importantly, you don’t need in-house people dedicated to the job.

Alternatively, you can go for entire families of applications that are interconnected 2 . Here you can just adopt a suite of applications for a domain in your business. Think, for example, of outsourcing your entire finance department’s technology to a vendor that has dedicated applications for each part of the department’s use cases.

You don’t only adopt a bunch of applications that are already interconnected to tackle a part of your business; you also adopt the best practices of a company that is an expert in the domain.

These applications come with a way of working that is aligned to the bigger domain they work in. In other words, they have hundreds of companies that trust them with handling (for example) logistics. That also means that they know a lot about logistics and have developed the best way (just by evolution and exposure of cases over the years) to do logistics. If you embrace these applications, part of the value proposition is that you are also adopting all this knowledge.

You can’t give your entire architecture away

Even if you tackle your entire landscape with 3rd-party applications, you will still need to connect these applications. Here again there are solutions in the form of enterprise service busses 3, but I’ve never seen an architecture where this works flawlessly.

I think it’s currently impossible to have an entire application landscape that is just 3rd-party applications. Be it that you don’t want to follow a vendor’s best practices, or cases where you just need to do something that the vendor doesn’t cover, or no longer covers.

There is also the case of vendor lock-in. With handing out ownership to vendors of your domain (or parts of it), you also give them power over it. It wouldn’t be the first time that a vendor held a company hostage with the dependency of the applications, all the while happily increasing the cost of the application/service.

Even if the relationship with the vendors stays in good spirits, what will you do if they stop innovating and a disruptor enters the space? Will you be able to transfer your data over to this vendor? Will your current vendor give you an easy way to get the data out? Will the new vendor even take the data, and in what format?

How I like to mitigate these issues

I think the most important part of this kind of architecture is keeping control over your data. Business logic is very important to a company, but it is something that can be changed and, in the worst case, be rebuilt. Data, on the other hand, is not something you can just reinvent.

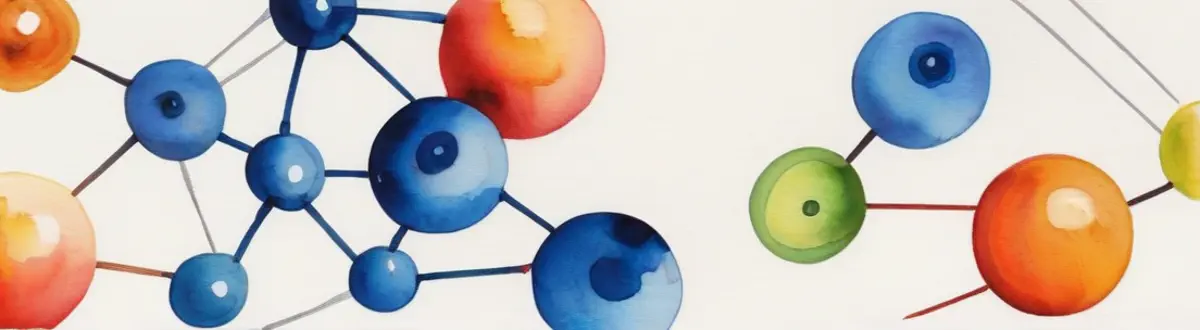

Another big issue, especially with best-of-breed architecture, is the wildfire of connections in your landscape. Every application needs data from different points; if you have a finance application, it will probably need information from your HR application, but also from your timesheet application and maybe your car leasing applications. Multiply that situation for most of your applications 4 in your landscape, and your architecture will be a mess. Removing or replacing applications in these kinds of landscapes are projects that could take up months to even years.

We can solve both of these issues by creating data hubs. These data hubs are central databases/data warehouses/data lakes that keep all the data from the domain. So, for example, in the HR domain, there is a central database that keeps all the data from the people that work in the company 5. This is the single source of truth of that domain. Now all the applications that need employee data would connect to that component. This might add extra connections to the environment (mainly sending data back to the datahub), but it will make the overall landscape way cleaner.

You now have these clusters of applications (like an atom with a neutron; the data hub and electrons; the applications) that all have their domain and a single point of data ownership. You can be sure that all the information is in a central place that you own and have full control over.

Not only that, but your analytics department will love you for it. They can hook their analytics tool into the data hubs and don’t have to connect to all the connections of the ESB 3 or all the other scattered databases around.

Moving to different vendors is now also easier. You are going to have to build or readjust to the new way of working (processes and business logic) in the new application, but the data is not a hostage. Even better is that you can easily start to integrate the new applications while using the old applications by just hooking the new application to the data hub and having real data. Testing in a hybrid way that doesn’t disrupt the legacy application while easing in the new application.

Another upside is that GDPR or privacy removal should now be easier, as you have one central place to purge the data. Ideally you can then feed the removal to the other applications, and as secondary data owners, the data would automatically be purged (in reality it’s often not that straightforward, but this method will definitely make it easier).

This all feels familiar

That’s because it’s not a new and novel idea. This is the same approach as a microservice architecture. The only big difference is that we are now not using microservices but 3rd-party services. The rest of the concepts stay the same. I know microservice architecture has its fair share of criticism, but mostly not for the central data ideas.

You could even go one step further and go for a hybrid setup here: fill the gaps in your vendor-based architecture with microservices. You then have the flexibility of very bespoke business logic with the ease of mind of vendor-based applications.

Well, that is on the condition that you aren’t too burned from the last time you tried a microservice architecture.

This is called best of breed. ↩︎

This is called Best of suit. ↩︎

If you are not familiar with them, they are connector applications: you connect them to endpoints, and they can transform and route the data. Often in a low-code interface ↩︎ ↩︎

At the scale we’re currently thinking of, this will be a few hunderd applications. ↩︎

Think of all the employee data: what business unit they are part of, their title, maybe even their picture, …. But not their financial data, like wage or financial situation. That data you should keep separate to keep it more private. ↩︎

further readings... in [Enterprise Architecture]

I think we should reimagine how we see architecture principles

To me, it always seems strange that in a world that thrives on innovation and constant change, every architectural department tries to …

Read EntryThe CMDB as an architecture source

Every company that I’ve helped start their enterprise architecture practice so far, always tell me that they might not have …

Read EntryChesterton’s Fence and paralysing your organization

Some years ago I worked at a place that had, buried deep in the codebase, a service running that combed through the central data warehouse …

Read Entry