How teams grow organically

I’ve been working a lot with service line architecture recently. If you’re not familiar with that; it’s how business units such as IT, HR, or Sales bring services to clients, both internal and external. These structures often mirror team organization.

Think of it as a hierarchy: IT at level one, Software Development and Ops at level two, and then individual teams, like: Software Team X or Ops Team Y, at level three.1

What’s surprising is how rarely these structures reflect reality. In practice, I often see people from multiple teams collaborating informally on projects. Even more striking, these same ad hoc groups reappear in project after project, suggesting a pattern that isn’t captured in the formal architecture.

If you’re a bit familiar with domain driven design, you might see some parallels with Conway’s law. And that is exactly what we’re going to talk about.

Conway’s Law

Organizations which design systems (in the broad sense used here) are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations.

This is Conway’s Law, most typically applied to software systems and products. In essence, products are a direct reflection of the communication patterns within the teams that created them. How they think, talk and view the world.

I want to take it one step deeper, I believe that organizations themselves are defined by these communication structures. As a result, the products they deliver inevitably embody those same patterns.

The challenge is that these communication networks are informal, fluid, and nearly impossible to map. Yet they are precisely what shape the outcomes.

How teams actually form

Here’s how it usually starts. You’re standing in line for coffee and run into someone from finance. A little small talk, a joke or two, and then they mention it’s tax season. They’ve hired a student to shuffle CSV files from one server to another by hand.

You blink. By hand? Why not automate it? You recall that Michelle from development built a similar integration recently, maybe you rope in a business analyst. Very quickly, what began as a casual exchange becomes the start of a new project. And a brand-new team.

This team doesn’t exist on any org chart. It emerges organically, based on who knows whom.

And once you’ve been part of a team like that, something else happens: the next time finance hits a snag, your name will be the first one they remember.

Communication patterns don’t just influence software design; they determine how teams themselves are formed.

The strength of weak ties

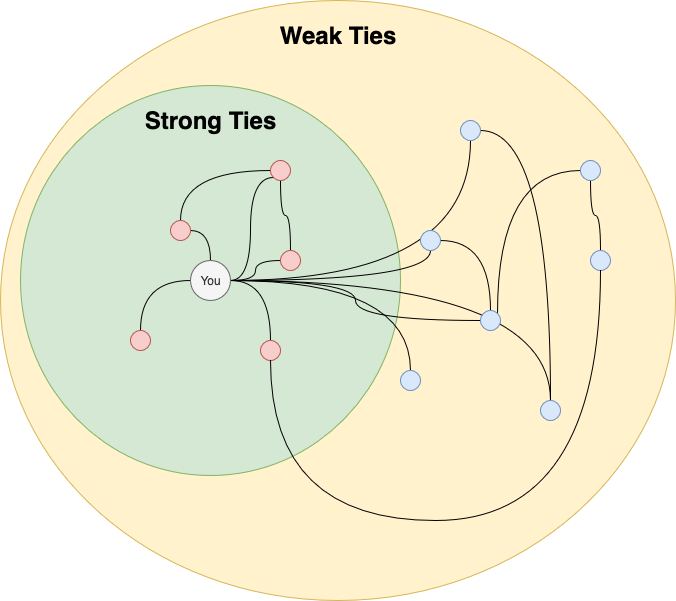

Sociologist Mark Granovetter described these casual, cross-cutting relationships as weak ties. In his seminal article, The Strength of Weak Ties, he distinguished between two types of connections:

Strong ties are the ones you lean on every day: your close friends, the teammates you talk with constantly. They’re steady, reliable, always in your orbit.

Weak ties are different. They’re the people you see now and then, the friend of a friend, the guy you bump into while waiting for coffee. They’re lighter threads, but they reach into places your strong ties can’t.

Your strong ties generally talk about issues and projects where you are also part of, your weak ties have an entire different world of projects. Where everyone in your strong tie group might have a strong opinion on Rust Vs Go, your weak tie connection might not know what an IDE is.

Here’s why it matters. If Conway’s Law says products mirror the way people communicate, then it’s these weak ties that organize these connections. They spark the ideas, highlight inefficiencies, uncover opportunities hidden inside silos.

And when those casual chats turn into projects, weak ties evolve into strong ones. That’s when the team forms, the solution takes shape, and Conway’s Law writes itself into code and process.

Is this a hidden pitch for back to the office work?

One of the best communicated teams I’ve ever worked on was scattered across the globe. Most of us had never met in person, maybe once a year, if that. And yet it worked. It worked beautifully.

The secret was communication, plain and simple. And the right tools to make it effortless. For us, that tool was Slack.

Slack wasn’t just for projects. There were channels for music, hobbies, random banter. You’d stumble into a debate about The Beatles versus The Beach Boys, and suddenly you were talking to someone you might never have met in your formal service line. Those side doors opened up connections that resulted in ad-hoc projects and innovations.

This design matters. I’ve consistently seen Slack foster such informal networks, but I’ve rarely observed the same in Microsoft Teams. Its structure tends to constrain communication, which, according to Conway’s Law, suggests something about Microsoft’s own internal culture.

That said, tools have limits. Large enterprises with thousands of employees cannot easily replicate the intimacy of hobby-based channels. And personal preference plays a role as well: I value face-to-face interaction, though I recognize that not everyone does.

The architecture you can’t draw

The big problem about all of this theory to my architectural mind is that you can’t formalize this stuff.

There’s no neat diagram that captures weak ties or coffee-corner alliances. But you can encourage it. You can make room for it to happen.

That’s part of the reason2 so many companies push for people to come back into the office, to spark those casual conversations again. And sure, there’s some truth in that. But let’s not forget the remote world. The tools we use every day shape how we connect.

Too often, they’re treated as an afterthought. Microsoft Teams may come bundled with your license, but convenience comes at a cost: missed connections, missed ideas, missed weak ties. And in those gaps, you lose opportunities that might have made all the difference.

I wrote more about this stuff, and how I don’t really like it here: https://frederickvanbrabant.com/blog/2024-07-12-business-capabilities-how-i-like-to-use-them/ ↩︎

There are also a lot of other reasons, some of them are not as positive ↩︎

further readings... in [people]

Systems Thinking in Enterprise Architecture

I first learned of systems thinking in the domain of city planning, and that is apparently also where the idea comes from. It was described …

Read EntryThe middle ground between canonical models and data mesh

Some years ago I worked with a scale-up that was really focused on the way they handled data in their product. They extensively argued over …

Read EntryThe CMDB as an architecture source

Every company that I’ve helped start their enterprise architecture practice so far, always tell me that they might not have …

Read Entry