Architectural debt is not just technical debt

When I was a developer, half of our frustrations were about technical debt (the other were about estimates that are seen as deadlines).

We always made a distinction between code debt and architecture debt: code debt being the temporary hacks you put in place to reach a deadline and never remove, and architectural debt being the structural decisions that come back to bite you six months later.

While I agree that implementing software patterns like the strangler pattern or moving away from singletons is definitely software architecture. Architectural debt goes way beyond what you find in the code.

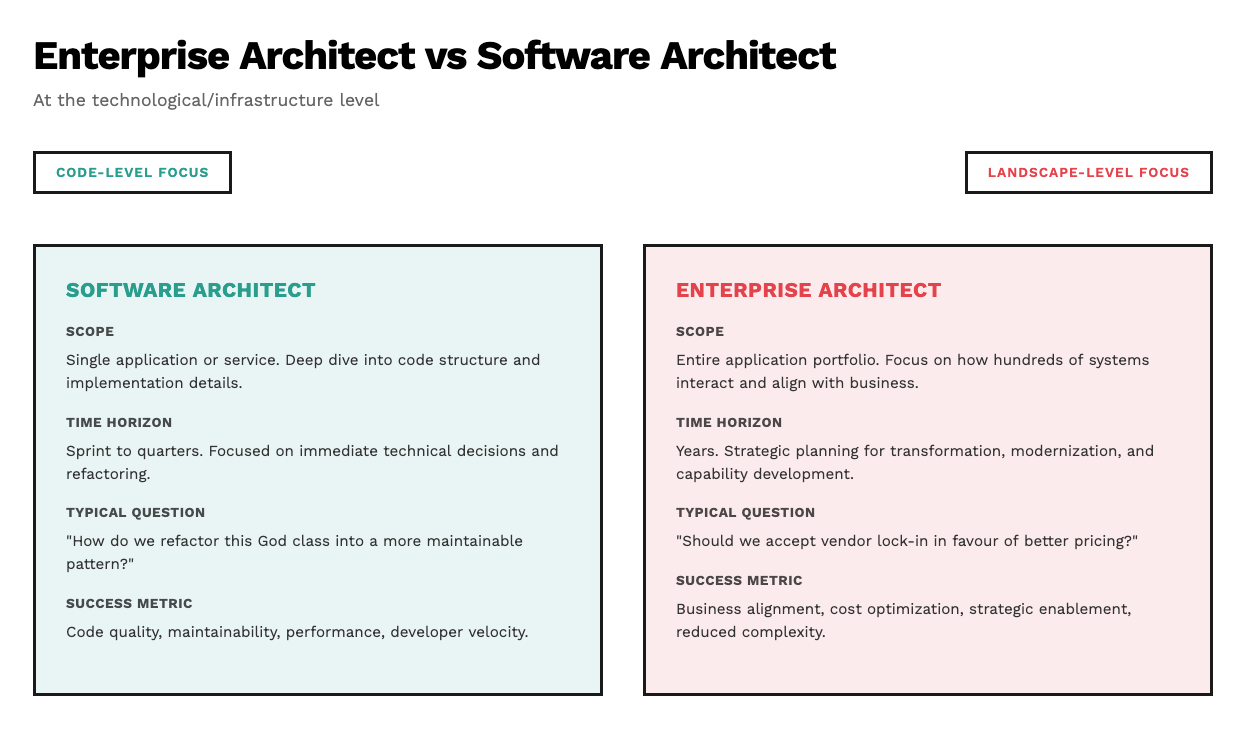

How I see technical architectural debt these days.

As an enterprise architect I still mostly complain about architectural debt and estimates that are seen as deadlines. That much certainly hasn’t changed.

These days, I’m less concerned with how the software itself works. That’s just not feasible when your organization has hundreds of applications 1. My main concerns are more about how these applications interact with the rest of the landscape. How the data flows, where data lives, whether there are bottlenecks, who’s going to maintain it, and what role will this application have in the future.

In an enterprise environment this is inevitable. There are so many applications and more than half of them are 3rd party SaaS applications. You need to keep on top of what you can control and let go of the parts you can’t.

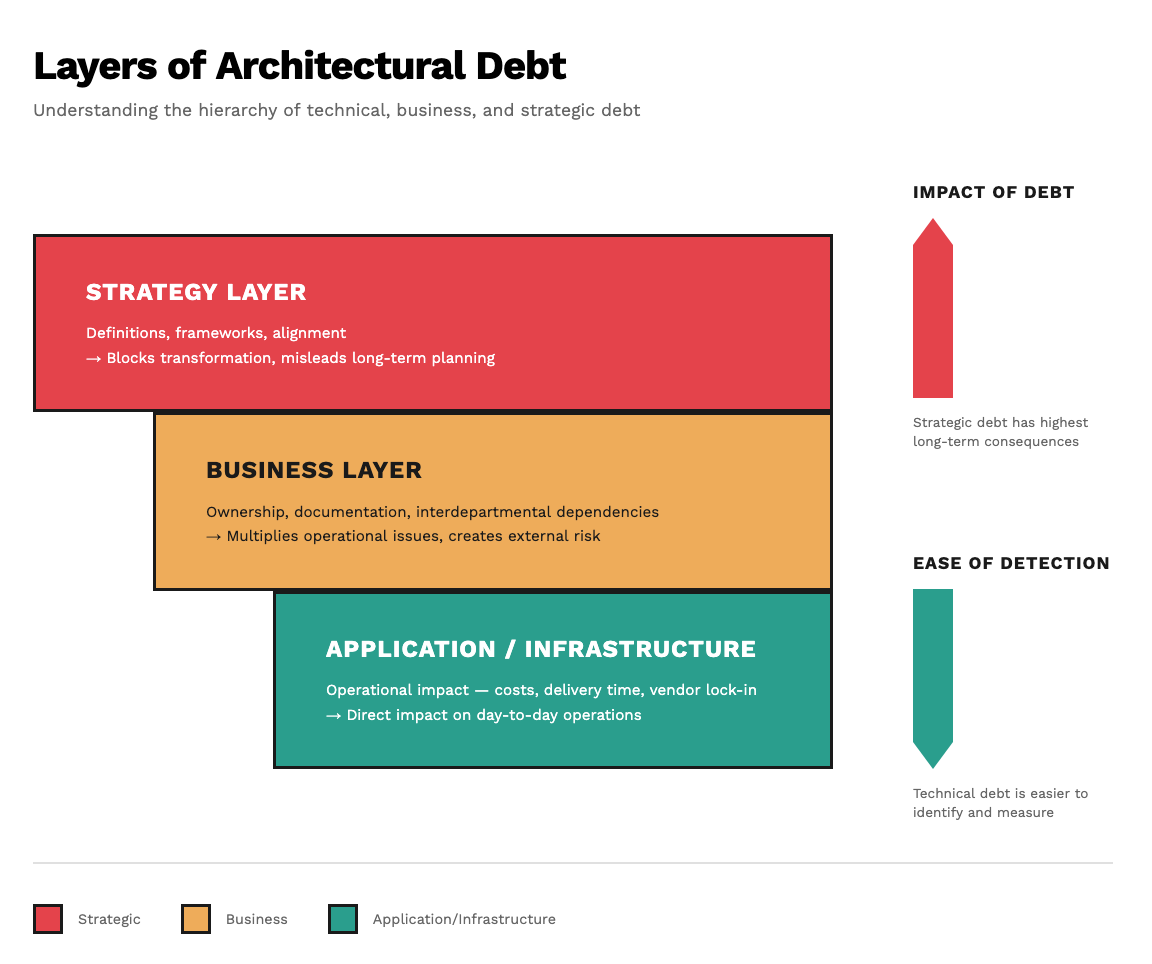

The layers of architectural debt

But architectural debt goes way beyond the technical layers. Enterprise architecture is not technical architecture 2.

And yes architectural debt can cost an organization a lot of headaches, but architectural debt on business and strategy layers can do even more damage.

Let’s dive into the issues at every layer.

Application / Infrastructure layer

As discussed in the intro, EA shouldn’t focus on the code level. I think that’s the job of software developers/software leads. They are in the code day to day, you are not. You can suggest software patterns or ideas (think event sourcing for applications that could be in the problem space), but they decide how they want to structure and maintain the code.

Instead, I focus on things like integration patterns. Do we still drop files over sFTP while also using a REST API? Maybe we can bring everything towards REST so we have a unified approach.

What about the systems we have running, what do they do? If there is overlap in functionality, then we can bring them together. Say for example file storage (a classic example). You might have free Sharepoint storage with every Microsoft account, but you might also rent storage space at AWS. Perhaps you could combine those.

And don’t forget about vendor lock-in. Finding the right balance between getting a discount for getting a lot of services from the same vendor, and them locking you in and holding your systems hostage behind huge migration costs is a real problem a lot of companies struggle with.

At this layer all the debt directly impact operations. Costs go up and time of delivery increases.

Business layer

Just like in the application/infrastructure layer we are not focused on the details. We don’t care about how many people work in what department and how the roles are defined.

What we are focused on is things like ownership and stewardship. If an application or process goes down, if there is a data leak, who are you going to contact?

Who are the people you need to get in a room if you want to modernize a department? Sure, you want to talk to the head of the department and the stakeholders of that department, but every department work with other departments. Just like applications, these processes, and flows are interconnected. You don’t want to modernize the processes of one department and break the day to day of five others.

What about outdated or phantom processes? If you give a new hire a business process overview to help them learn their role, and that documentation is wrong, that’s unpleasant. What’s even more unpleasant is if instead of a new hire, it’s an auditor.

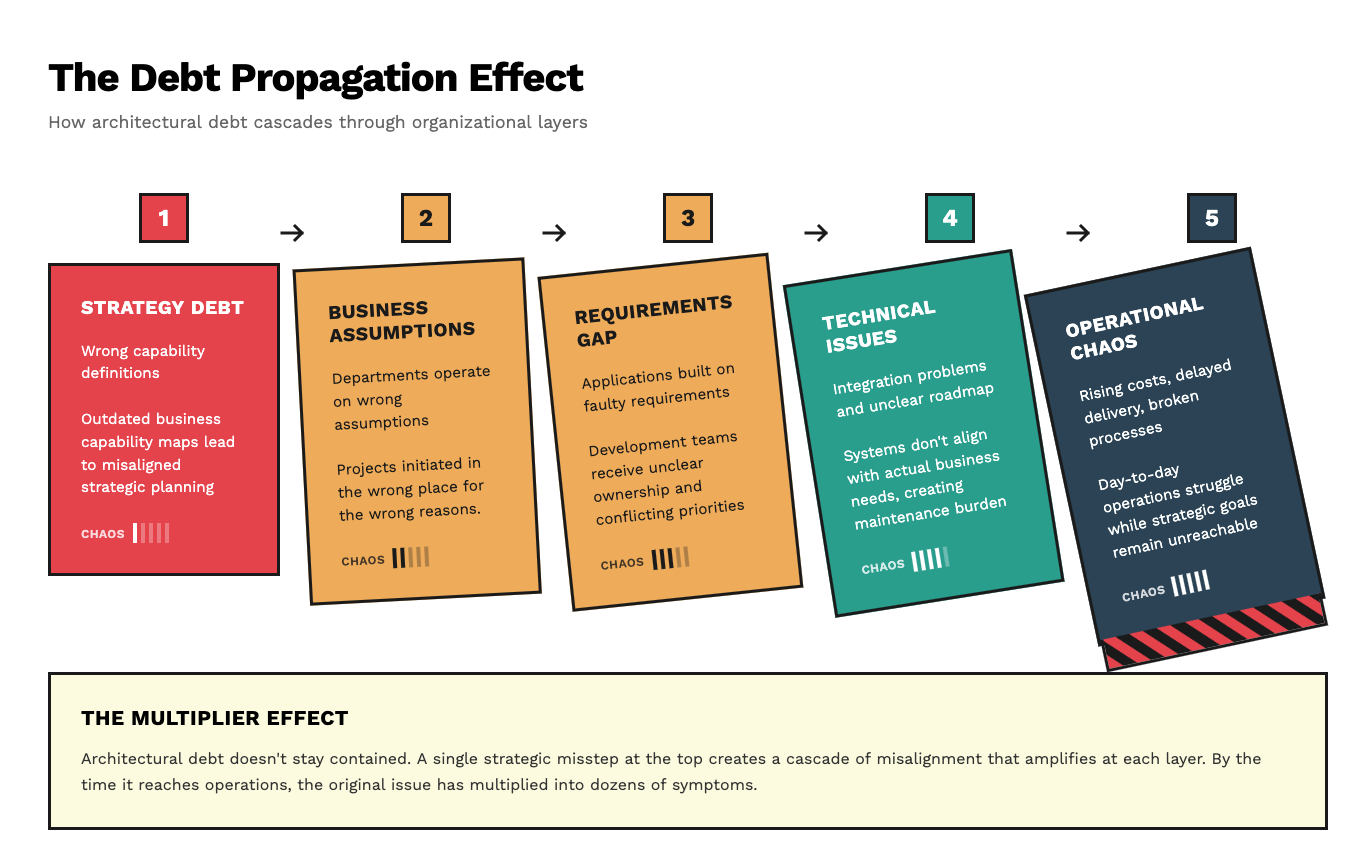

So at this level it’s more about documentation. Outlining how departments work, who does what and what they need to do their job. If people work under wrong assumptions, they will also start projects under wrong assumptions. They will already be on the back foot before they start.

So here again it’s about cost and outside risk. Issues here will multiply issues on the operational side.

Strategy layer

An enterprise architect doesn’t build strategy, they assist the people that define the strategy.

To do that however, you need to have your rows in order. The better insights you can provide, the better the outcome (potentially) will be.

The main issues of debt here are mis-definition and half frameworks. I’ve waxed on and on about the value of Business-Capability maps3 for this exact reason.

If you want to understand what your organization is good or bad at, you can do a business capability maturity map. A huge exercise where you go over every capability and rate them with a scoring of chosen parameters.

Every capability now has a score, and we can start looking at what areas we need to focus on and improve (if they fit in our strategy for where we see the company).

Great! But what if we defined the capabilities wrong? Maybe the map is outdated, or it’s not a capability map at all but just a silo’d business department overview. In that case, you’re going to base your strategy for the next 3-5 years on wrong assumptions.

Debt at this level can have enormous long-term consequences. This is what blocks transformation exercises and could even make bad long term strategy look appealing.

Tackling architectural debt

Luckily, there’s some good news: unlike developers, enterprise architects have the time and visibility to flag architectural debt. We have the time and resources to create dashboards and gather proof of what is going on. We also have access to the right people where we can plead our case to.

And that is also how and what we should do. Showing misalignments to a CIO or COO is easier with a PowerPoint or dashboard, than with a God class that you want to refactor into a command-bus pattern.

Keeping stock is key. I have in my architecture tools clearly laid out what I consider debt. I also have a list in my notebook of things I want to tackle and the order in what I want to tackle them in.

Building that case is bringing all the data you have gathered together, an AS-IS and a TO-BE, and a business case of what the improvements would be, and the risks of not handling it.

From there, it’s mostly about picking your battles. There are places where it’s easier to tolerate architectural debt, think for example of a system of innovation versus a system of record. 4 You can tolerate it more in innovation projects than on core sources of truth. On the condition that they’re handled once the innovation period is over.

Also be prepared that most often you will get the answer: OK, you can go out and fix it. So be sure you have the bandwidth to actually go out and fix it. The debt will not just disappear by you just flagging it.

I wrote about the abstraction you have to make here: https://frederickvanbrabant.com/blog/2025-01-17-turning-complexity-into-manageable-complication/ ↩︎

https://frederickvanbrabant.com/blog/2025-04-14-avoiding-vague-hand-waves-what-is-enterprise-architecture/ ↩︎

- https://frederickvanbrabant.com/blog/2024-07-12-business-capabilities-how-i-like-to-use-them/

- https://frederickvanbrabant.com/blog/2024-12-23-enterprise-architecture-is-really-bad-at-architecture-strategy/

- https://frederickvanbrabant.com/blog/2025-03-09-enterprise-architecture-skunk-works/

https://frederickvanbrabant.com/blog/2025-08-10-pace-layering-an-application-portfolio/ ↩︎

further readings... in [Enterprise Architecture]

Choosing your starting line in enterprise architecture

I’ve been part of the creation of five enterprise architecture offices in my life. Some I’ve led, others I’ve simply been part of.

If …

Read EntryThe death of the enterprise service bus was greatly exaggerated

Every six months or so I read a post on sites like Hackernews that the enterprise service bus concept is dead and that it was a horrible …

Read EntryWhat is a Value Stream and how does it relate to a Value Chain

Organizations often use “value stream” and “value chain” as interchangeable labels. It’s not the biggest architectural drama in the …

Read Entry